Willamette Pass Ski Patrol History

Ski patrol’s history parallels that of its mountain

By Joe Mosley

With research contributions from Rich Maris and Lane Hoxworth

the 1972 Willamette Pass ski patrol pose for a photo.

We still don’t know which came first, the chicken or the egg. But here’s the answer to a similar conundrum: the Willamette Pass Ski Patrol actually does predate the Willamette Pass Ski Area.

The Willamette Ski Patrol — parent of both Willamette Pass Ski Patrol and Santiam Pass Ski Patrol — was born in December 1938, just months after the National Ski Patrol was formed by Charles Minot Dole.

There you have it.

It’s true that the U.S. Forest Service authorized the Upper Willamette Winter Sports Association to begin clearing timber and brush from McFarland Butte — now known as Eagle Peak — in 1941, which is a year before Willamette Pass Ski Patrol distinguished itself from the original organization. But it would be 1945 — another three years after the home mountain got its exclusive ski patrol — before the Forest Service contracted with a concessionaire for the ski area’s first permanent rope tow.

“The Obsidians (hiking and outdoor club) are the ones that actually started the ski patrol,” said former Willamette Pass Ski Patrol member Bill Temple, whose uncle, Roy Temple, was a founding member of the patrol and operator of that first ski tow.

“The main (place) people went skiing at was up the McKenzie Pass — they set up a rope tow up there,” Temple said. “Then when (Highway 58) got punched through, Roy Temple started the Willamette Pass Ski Area.”

The National Ski Patrol has no archives to document the history of individual patrols, but the early emergence of WPSP tends to support a bit of local trivia — that the “035” prefix in the NSP numbers of Willamette patrollers means they are part of the 35th patrol to join the national organization.

Did someone mention trivia? How about the fact that the By George run at Willamette Pass is named after George Korn, who owned the area from 1949 to 1962? Or that Swoosh! is a clever reference to the early Nike investments of the Wiper family, and June’s Run is named in honor of Tim Wiper’s mother; Good Time Charlie for his dad, Charles Wiper; and Sally’s Way for Tom Wiper Sr.’s spouse at the time. Did you know that RTS really does not stand for Really Tough … anything? It was named for Richard T. Satagaj, an owner of the area in the early 1980s. Amber’s Way and Lois Lane, both located at the bottom of RTS? Those are named after Satagaj’s daughter and wife, respectively.

“There’s a history to all the runs,” said Dave Brown, who joined the patrol in 1977 and was its director on three separate occasions, for a total of 11 years.

And the histories of the mountain and the patrol are hopelessly intertwined.

The early Willamette Ski Patrol was organized by the Obsidians and a group called the Eugene Ski Laufers, and patrolled informal ski sites — some with portable rope tows and some without — in both the Willamette Pass and Santiam Pass areas. Members of the patrol were required to take a first aid class from the American Red Cross, which donated — get this — a first aid kit!

“Skiing became really popular in 1936 or 1937, and they had a special train that would leave on Saturday morning or Sunday morning and go to the Crescent Lake area,” Bill Temple said. “They had a rope tow set up on one of the hills up there, and that’s where they originally did the skiing.”

A December 1938 story in The Eugene Register-Guard mentions a “ski train” that took as many as 600 Eugene skiers per trip to Crescent Lake, where residents had built a 1,000-foot-long, 100-foot-wide ski run. But no mention of a ski lift or tow.

The original patrol building was elevated off the ground.

The Obsidians bought their first portable rope tow in 1940, for $342.50, according to the group’s newsletter. Its 1,200 feet of rope cost another $14.

Clearing began at Willamette Pass a year later, and a tow at the newly opened ski area — maybe the Obsidians’ portable one — is mentioned in The Register-Guard as early as March of 1942, about the same time the Willamette Pass Ski Patrol was separating itself from the Willamette Ski Patrol. According to the newspaper story, all-day tickets were 50 cents for the rope tow, described as “about a block and a half from the top of the tow on down to the shelter … a sporty little trip.”

The Obsidian — monthly newsletter of the club by the same name — reported that the overall Willamette Ski Patrol (Willamette and Santiam) had a nucleus of 11 members in 1945, with its fluid membership expected to hit about 30 during the ski season. And the newsletter reported a year later that the patrol had cashed in during its annual fund drive, by raising a total of $417.

In 1947, the combined Willamette Ski Patrol competed at Mount Hood against other Northwest patrols in what The Register-Guard described as a “toboggan race.” Hmm. Two-person teams ran their sleds from “the top of Ottog Lang Hill” to the lodge, administered aid to a mock patient that Willamette patroller George Souza described as “so badly injured we should have dug a hole and buried him in the snow,” then loaded the patient and transported him down “Pucci’s Glade.” With teams judged on speed, safety and first aid ability, the two Willamette entries finished fourth and sixth. And they drew an editorial comment from The Register-Guard: “We think they did real well and deserve a cheer.”

Sign from the original Gene McMurphey shelter.

Gene McMurphey, who was Souza’s partner in the Mount Hood toboggan competition, was killed in an industrial accident a year and a half later, and the Gene McMurphey Memorial First Aid Shelter — the first patrol building at Willamette Pass — was completed in 1951.

Meanwhile, George Korn had purchased Willamette Pass Ski Area in 1949, and went big time in 1959 by purchasing the 3,000-foot poma lift that would be a Willamette Pass fixture well into the 1970s. The lift cost $50,000 and was installed in 12 days.

Bill Temple joined the patrol in 1955, and remembered the patrol building being “a half a story off the ground.”

“I was from Lebanon and mainly skied at Hoodoo, but I ran across (Orville) Caswell (an early Willamette Pass patroller), and Ory talked me into joining the ski patrol,” Temple said.

Despite being a small patrol from a small ski area, WPSP still managed to make a splash in the much bigger pond of the National Ski Patrol. Four Willamette Pass patrollers were asked to serve as NSP patrollers for the 1960 Olympics at Squaw Valley, and three accepted. Caswell declined his invitation, but Allan lindley, John Quinner II, and John Nasholm represented Willamette Pass on the Olympic stage.

“I think there were more from Willamette than just about any other patrol,” said Temple, who served as WPSP’s leader a couple of times before transferring to Mount Bachelor, where he patrolled until the late 1970s. “I must have left (Willamette) in ’63 or ’64 — the same year George Arnis took over the area.”

Arnis — who also ran a ski school at Willamette, in conjunction with The Register-Guard — actually took over operations at Willamette Pass in 1962, when a group of 10 Cottage Grove teachers purchased the ski area from George Korn for $55,000. That was the start of a tumultuous 20 years for the ski area, with at least eight ownership changes, two or three seasons when the area remained closed and one period when the ski patrol was replaced by management employees.

Bill works the original poma lift.

“Not only did we have a revolving door of owners, but we had some real bad snow years,” said Hal Duncan, who joined the patrol in 1972. “On By George, where you got off the poma lift, there were times we had to take our skis off and walk on down the hill. It was solid mud. But it picked up, and it did get better.”

The Cottage Grove teachers owned Willamette Pass until 1968, when their initial $55,000 investment had grown to a debt of $100,000. The Eugene-Lane Teacher’s Credit Union — which later became SELCO — took over when the teachers were unable to make payments, and operated the area for a year before it was purchased by Keith Hedeen.

Hedeen immediately faced pressure from the Forest Service over complaints from skiers about sanitary and equipment problems. The forest ranger at the time reportedly threatened to shut the area down for good. Hedeen and Billy Willis, a minor shareholder, put together a funding and improvement package that allowed the area to open for the 1969-70 season. It included a new poma lift cable, new rope-tow ropes, new rental gear and a contract with a company to run the restaurant. During the three years of Hedeen’s ownership, he worked to improve the hill by removing obstacles. The U.S. Marine Corps – through efforts of the Willamalane Park and Recreation District – was commissioned to stage demolition drills at the ski area, blowing up stumps and snags to allow possible earlier openings with lower snow packs.

But it was while the teachers owned the area — and Arnis operated it — that the ski patrol had its only hiatus in its decades-long relationship with the ski area. It happened during February of 1967, when WPSP leaders pulled their members off the hill in a dispute that began when the area manager converted their patrol building to other uses.

“The ski patrol contends its national standards were jeopardized when the building it used for its operations was turned into a multipurpose building by Arnis,” according to a Register-Guard story about the spat.

The disagreement was eventually resolved, and patrol members returned to both the mountain and their patrol room. But a similar difference of opinion over boundaries between the patrol and area management also led to a break in service years later for Duncan, who was patrol director at the time.

“I can’t tell you the owner, but at one time the Willamette Pass Ski Patrol had $3,500 in the bank, or something like that,” Duncan said. “But the owner (of the ski area) wanted it. I said ‘no,’ and he objected, so I couldn’t be ski patrol director that year.”

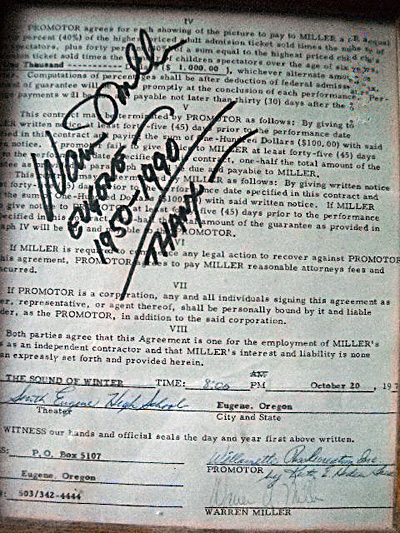

Ski movie pioneer Warren Miller came to South Eugene High School in 1970 for a film showing that benefited Willamette Pass Ski Patrol.

Duncan said the same owner built a shed in front of the old patrol room to house a hot tub for his private use.

“That building is now part of the existing patrol room,” Duncan said.

Turmoil at Willamette Pass hit its high point during the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the ownership went from SELCO to Hedeen, then to Hoodoo Ski Bowl, to Mike Neary, back to Hoodoo and finally — in 1980 — to Richard and Lois Satagaj (of RTS fame).

The ski area had been closed due to lack of snow for at least one season during the Cottage Grove teachers’ ownership, and Hoodoo kept the area shuttered again during the 1976-77 season as another buyer was sought.

Neary bought the ski area but struggled from the beginning, and Willamette Pass remained closed again for the 1979-80 season as Hoodoo took over in a foreclosure action.

That was a turning point for the ski patrol. Some of its members accepted an offer to transfer to the Hoodoo patrol, and the few who remained waited for ownership conditions — and snow conditions — to improve.

“They just wanted someplace to go ski,” said Brown, who stayed at Willamette along with Duncan and a handful of others. “And (Hoodoo) had a chairlift.”

Yes, Willamette still had only its poma lift and a rope tow or two, and skiing terrain was limited to By George and a meandering haul road. Brown remembered the black grease that accumulated on the poma lift platters, and said whenever he went to other ski areas people would look at the seat of his pants and say, “Oh, you’re from Willamette.”

Duncan recalled another unpleasantness from the poma lift days. The springs on many of the pomas had worn out, and when a lift rider put one between his legs and took off, there was often a surprise in store.

Hal Duncan works in the Patrol Aid Room.

“Men did not want to ride that poma lift,” Duncan said. “You’d wait, and that thing would pull you a foot in the air — and it was not a comfortable feeling.”

Patrollers Larry Cox and Ron Wilson were among the contingent that put Willamette’s poma lift behind them and headed for Hoodoo and its up-town chairlift in 1979.

“Rather than not going (skiing) for a season, Santiam welcomed several of us over there,” Wilson said. “I think it was for two years.”

“I came back in 1982,” Cox said. “But I had given Hoodoo a commitment because I was on their board. So I was on both rosters until 1984, I think it was.”

During their absence, the Satagaj family purchased the ski area. The new owners got Willamette Pass up and running, and headed in the right direction. But like previous operators, they ran the place on a shoestring.

“Lois Satagaj had a little restaurant there (the Summit House, in what is now the patrol building), and Rick ran the mountain,” Duncan said. “They did the best job they could possibly do, without any money.”

During the 1981-82 season, the Satagaj family took on Charles Wiper, Jr., and his family as partners, and the Willamette Pass Ski Corporation was formed. The following summer — in the first of several investments by the Wipers — a double chairlift was installed to carry skiers for the first time to the top of Eagle Peak.

That meant an influx of skiers, which would require reinforcements for a suddenly short-handed ski patrol. Those who had gone to Hoodoo were invited back, and several accepted.

“We needed patrollers badly, and Santiam didn’t,” Duncan said. “All those people were really top-quality patrollers. We didn’t have a problem with them going off, and when they came back, I was a happy camper.”

“Some of them came back from Santiam, and we started growing the patrol,” Brown said. “They came in waves, and a lot of them are still here.”

The modern era of both the ski area and its patrol had begun, but that doesn’t prevent a little nostalgia from those who lived through the earlier days.

“Knee (injuries) and tib-fibs were very common back then, and there were back injuries, too,” Wilson said. “It wasn’t uncommon for a beginner to come up with old leather straps on old wooden skis, so when they fell, nothing released.

“It was also not uncommon for us to load someone on a backboard into the back of a station wagon (for a non-ambulance trip to the hospital). We didn’t have the paramedics and professional medical folks that are attracted to the patrol now, but we had some good skiers and some classic, devoted patrollers.”

And they all took a hand in guiding the patrol — more or less.

“There wasn’t a board of directors that was active in formulating policy so much in those days,” Cox said. “We just had monthly meetings (of all patrol members) to hash things out. But those didn’t accomplish that much.”

The patrol’s duty-day rotations were similar to those used now, but to Cox that was immaterial. “It didn’t matter to me, because I was there every day, anyway,” he said.

The original lodge, decorated for carnival, now used as the patrol aid room, ski school basecamp and Willamette Pass dispatch.

By 1983, the now-flush ownership group was ready for more moves. The Satagaj family left Oregon to develop a ski area in Pennsylvania, and the Wipers took control of Willamette Pass. They built the current-day lodge and added the Twilight Chair, opening Willamette’s first substantial terrain for intermediate skiers.

The Midway and Summit triple chairs replaced the original double chair in 1987, and the Sleepy Hollow chair was added the same year. Peak 2 expanded skiing to the mountain’s north side five years later, and the high-speed Eagle Peak Accelerator replaced the Midway and Summit chairs 10 years after that.

The old, A-frame ski patrol room is long gone — moved to Crescent Junction, in fact, where it was made into an apartment. The patrol room was moved to the ground floor of what used to be the ski area’s lodge.

With the mountain’s growth came a variety of features, promotions and events, from bonfires to barbecues, from Ski Wee to Freeheel Frenzy and from high school races to, well….

The Willamette Pass growth boom was punctuated in 1993 by an event called the Subaru U.S. Speed Skiing Championships. It was held on RTS — considered one of the nation’s steepest ski runs (52 degrees at its steepest) — and produced a top speed of 116.56 mph.

Brown, the former patrol director, said it also produced injuries including a ruptured spleen, and resulted in the first helicopter landing on the run-out of RTS.

Brown and others who patrolled through the old times were duly impressed by what had occurred both on the mountain and in the patrol over the previous 30 years — particularly by the unprecedented growth and stability. They also had an appreciation for those humble beginnings.

Speed Skiers skiing down the RTS speed course.

“(The patrol) was actually very organized,” Wilson said, recalling the group he joined. “It was very small — I think it was like 20 people or so. But it seemed like we were always doing something to help keep (the mountain) open.”

Brown remembered the ski patrol leading the way for the mountain.

“(Ski area operations) were a mess,” he said. “We were the constant part of it — the ski patrol was the stable part.”

The patrol continued to be stable, and the ski area followed suit when brothers Charles Wiper, Jr., and Tom Wiper, Sr., bought a 60 percent share of the resort in 1981 and promptly spent another $750,000 on the ski area’s first chairlift and other improvements.

A story in The Register-Guard just prior to the 1982-83 season told the story: “Willamette Pass, the poor stepchild among Oregon ski areas, moves into the big leagues this season with its first chairlift, new runs and hopes higher than its renamed hill.”

That new name was Eagle Peak, and the Wipers remained committed to the ski area as they assumed control of the entire company, expanded and made various improvements, and passed reins to the company from Charles Wiper to his son, Tim.

It all began as the Hult Center for the Performing Arts was opening in Eugene, and Brown remembered the rebirth of Willamette Pass as the Wiper family’s legacy of choice.

“Tim’s dad made comments something like, ‘I don’t want to have the Hult Center named after me,’” Brown said. “He said, ‘I’d rather do something I enjoy.’”

Into the 21st Century

By Jan Lafeman

Over the years, the qualifications for patrollers evolved into two years of rigorous medical and toboggan training. Long gone were the days of the 1950s when there were two requirements: Be a good skier and take a first aid class. Passing the National Ski Patrol’s Outdoor Emergency Care program was comparable to passing an Emergency Medical Technician program, and some said it was actually more difficult. At Willamette, the medical OEC training and toboggan (Outdoor Emergency Transportation) training became a two-year process that involved countless volunteer hours for both candidates and their instructors.

By the early 2000s, the Willamette Pass Ski Patrol had grown to about 100 weekend volunteer and weekday paid patrollers. In 2001, Dave and Kay Lee Brown established a youth program for high school students. The teenagers became an integral part of patrol and assisted with run reports, sled packs, opening and closing duties, and shovel work...lots of shovel work. The Ski Patrol Youth (SPY) program later became a model for the National Ski Patrol’s Young Adult Patroller program. The teens learned about responsibility, leadership and patient care. Some went on to become valuable adult members of patrol. Mindy Ingebretson-Wolowicz joined the SPY program in 2002, then ended up becoming the youngest pro patrol chief in ski world memory. She was eventually hired in 2023 to run the whole resort.

SPY founder Dave Brown died in 2018. He left a legacy of patrol wisdom for a new generation at Willamette Pass, as did others interviewed above including Larry Cox (died 2020) Hal Duncan (2022), and Bill Temple (2025).

In 2014, Willamette established a mountain host program. The hosts helped the resort with customers, and also aided patrol with duties that did not involve the extensive medical (OEC) and toboggan (OET) training required for patrollers. The host program, like the SPY program, became an additional source of recruitment for future patrollers.

Gino Grimaldi and Dan Nicholson model 3D printed masks used during the pandemic. Photo by Laurie Monico.

In March of 2020, the Covid 19 pandemic shut down Willamette Pass. Both patrol fundraisers -- the summer Waldo 100k and the fall ski swap -- were cancelled while an anxious world waited for vaccines. Most patrol training ceased. The pass opened the following season with mask mandates, a closed restaurant, and “social distancing” rules that kept patrollers mostly out of the patrol room, holding meetings in blizzards and eating lunch in their cars. When treating patients, patrollers wore 3D-printed masks that made them look like characters out of “Star Wars.” Resort management hauled an old chairlift engine house to the top of Eagle Peak to create a bump shack that would isolate patrollers from the lift operators.

The pandemic, along with an amazing snow year, brought large crowds including many first-time skiers and snowboarders. “These numbers remind me of the Willamette Pass of 10-15 years ago!” longtime patroller Andy Bechdolt wrote in the patrol newsletter. “Lines stretching from the base of EPA to the intersection of Perseverance and By George. Skiing is one of the few things that people could actually do this winter, so it seems like EVERYONE decided to “give it a run,” he wrote.

The pandemic prompted the installation of an EPA bump shack (an old lift engine house) in 2021. Photo by Jack Lafeman.

The pandemic continued to affect patrol protocol and operations for two years. As the global crisis eased and started fading from memory, the recycled bump shack remained a popular addition to the ski area for patrollers.

In 2022, resort owner Tim Wiper entered a business partnership with Mountain Capital Partners. MCP, a private equity company, was rapidly acquiring small, struggling ski areas in Colorado and the Southwest, as well as larger resorts in Chile. Willamette Pass was its first investment in the Northwest. The company pumped about $1 million into operations initially, including new rental gear and expanded snow-making capabilities. Within two years, changes included an upgrade from diesel to electric power for Peak 2; the resurrection of the Midway lift that had been idle for years; and an increase from a five-day to a seven-day-a-week operating schedule. The resort opened the lodge balcony for sunny spring days and hosted special events including its first annual pond skim in 2025.

Patroller Amber Travis takes a run at the first annual pond skim at Willamette Pass in 2025. Photo by Ian Doremus.

MCP brought its “dynamic” ticketing system to the pass. The first year, it advertised prices starting as low as $9 per day for the limited number of savvy customers who bought online in advance. Prices then increased based on demand — the more tickets sold, the higher the price. When the window pass price approached $100, patrollers knew it would be a very busy day. MCP also offered free skiing for children 12 and younger, drawing families away from Mt. Bachelor and Hoodoo ski resorts. Both those resorts soon changed their age caps for free skiing in order to compete with the revamped and newly popular Willamette Pass.

The investments and marketing strategies worked. In 2025, Willamette logged its most financially lucrative year ever and recorded more than 100,000 skier visits, another resort record. Daily skier counts reached as high as 2,500, in contrast to the previous decade when customer counts were often lower than 500 and sometimes measured only by the dozens.

“It was the most successful year we’ve ever had on the books,” General Manager Mindy Ingebretson-Wolowicz said. “Now the pressure’s going to be on to do it again next year,” she said on closing day May 4.

The influx of guests brought an increase in injuries and other calls for help, taxing resources and challenging patrollers both physically and emotionally. The pass had its first skier death in 18 years. That fatality and an earlier car-accident death of beloved patroller Amy Samson made for a bittersweet season of triumph and tragedy. Still, the patrol and the new management team had high hopes for another new era at the pass.

The following links include news stories about Willamette Pass from 1930 to 2012. Compiled by Rich Maris, these 300 pages chronicle the colorful history of the pass for those who enjoy diving into the details.